Ice Ice Baby

Ice has been on quite the rollercoaster ride when it comes to support in medicine. The once popular treatment has recently undergone scrutiny, largely because of self-titled ‘The Anti Ice Man’ Gary Reinl’s publication ‘Iced’. Because of Gary’s work, many wrongly believe the medical use of ice originated in 1962 when surgeons used ice to preserve a boy’s arm that had been ripped off in a freight train accident. The use of cryotherapy actually dates back thousands of years, having been documented as early as 3500 B.C. in the Edwin Smith Papyrus. It continued to be practiced and documented by Baron de Larrey (a French army surgeon during Napoleon’s Russian campaign) in 1812, Temple Fay (an American neurosurgeon) in 1938, and Irving Cooper (an American neurosurgeon) in 1961. Despite the long history of therapeutic cryotherapy, it remains controversial in today’s practice. Many recommend its use without thought or research. Others passionately discourage the application, claiming that it slows the healing process. So, which is it, is ice amazing or terrible?

Edwin Smith Papyrus

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is an ancient Egyptian medical text, named after Edwin Smith who bought it in 1862, and the oldest known surgical treatise on trauma. From a cited quotation in another text, it may have been known to ancient surgeons as the "Secret Book of the Physician".

Before we determine whether ice is the world’s best or worst treatment (or more likely, somewhere in between), we have to understand what ice does and does not do. The main reasons people use ice is that they believe it reduces inflammation, relieves pain, and allows for a quicker return to play. Afterall, ice is the second treatment in Dr. Gabe Mirkin’s R.I.C.E. protocol, which has become a mainstream treatment of athletic injuries. The most obvious effect of ice, which is often overlooked, is that it decreases tissue temperature. While this point may seem trivial, it becomes important when considering the broader context of how ice works. For example, because the skin is most often in direct contact with the ice, it cools rapidly. However, because the muscle is deeper within the body, it does not cool as quickly as the skin. Keep this point in mind when exploring the other effects of ice. Another effect that is fairly clear within the literature is that ice causes vasoconstriction of the blood vessels, which subsequently decreases blood flow and inflammation. In simpler terms, ice makes your blood vessels narrow, making it harder for blood to flow. Lastly, one of the most clearly understood benefits of ice is that it decreases pain. It accomplishes this by slowing down nerve conduction velocity. While all of these micro-changes are not perfectly understood yet, the scientific community has a good start to learning about them. The problem that many athletic trainers are facing is that we don’t know much about the macro-changes. Does decreased tissue temperature lead to more rapid healing or recovery? Does decreased blood flow and inflammation promote faster return to play? Does decreased pain fix anything in the body, or is it necessary for safety?

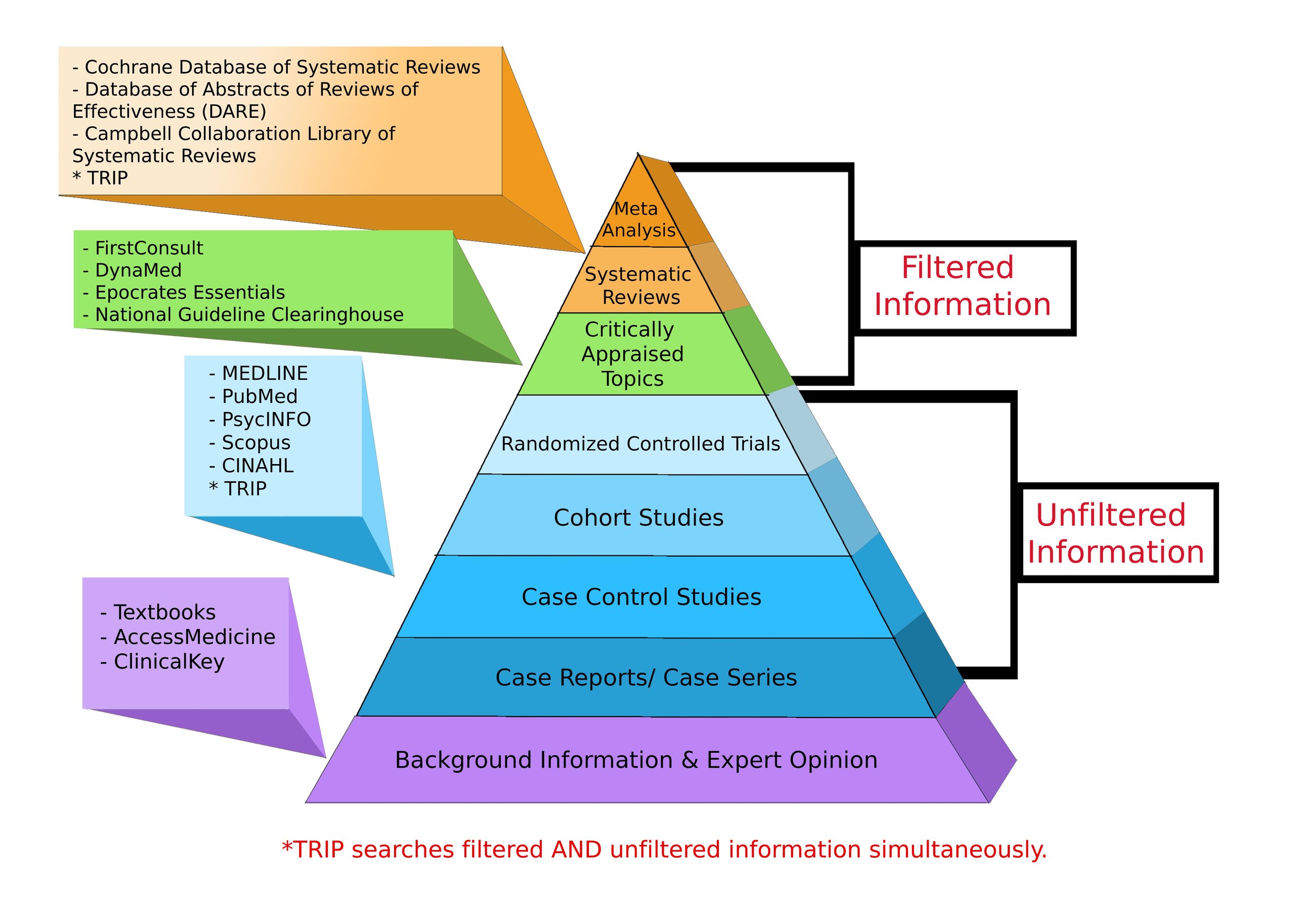

Perhaps the best study to date regarding macro-changes was a systematic review published by the Journal of Athletic Training in 2004 (A systematic review is a summary of evidence, typically conducted by an expert or expert panel on a particular topic. This is one of the highest standards for scientific research and overrules any individual’s expert opinion. For reference, the levels of evidence pyramid can be found below). They found that ice decreased return-to-play time, which would support the use of cryotherapy. Additionally, another study by the Journal of Athletic Training stated that ice limited swelling in the short-term (up to one-week post-injury). When we combine all of these beneficial effects (decreased swelling, decreased return-to-play time, decreased pain), it doesn’t take a systematic review to tell us what we all know — ice can help athletes feel better post-injury and will therefore speed up return to play.

Levels of Evidence Pyramid

The levels of evidence pyramid provides a way to visualize both the quality of evidence and the amount of evidence available. For example, meta-analyses and systematic reviews are at the top of the pyramid, meaning they are both the highest level of evidence and the least common. As you go down the pyramid, the amount of evidence will increase as the quality of the evidence decreases.

Perhaps the last question we need to ask regarding ice is an ethical one: is a faster return-to-play good? Coaches and athletes often pressure athletic trainers to allow athletes to play as soon as physically possible. However, there are some concerns with this system. Namely, rushing the return-to-play can create biomechanical compensations that will lead to further complications of the initial injury or can create other injury elsewhere in the kinetic chain. I will leave this question unanswered, as it is not as clear to me as the literature encompassing the use of ice after injury.

All this being said, what are my recommendations for the use of ice? I recommend ice in the acute inflammatory phase (first 2-3 days, see chart below). This can help the athlete to feel better because of the decreased pain and limits the swelling and inflammation, which will later create decreased range of motion. After 2-3 days, I only recommend ice if the athlete is experiencing pain. Once inflammation is decreasing, function takes precedence over protection. Depending on the nature and severity of the injury, I suggest working on range of motion as soon as tolerable to allow for functional benefits (increase range of motion and maintain strength). Once full function has been restored (range of motion and strength), you can begin working back into athletic exercises (running, jumping, cutting, etc.).

Stages of wound healing

I hope this writing has been helpful for you and clarifies the use of ice in athletic injuries. Feel free to discuss this article or the use of ice with me via any of my social media links at the top/bottom of the page or in the comments section below.

Ice has been on quite the rollercoaster ride when it comes to support in medicine. The once popular treatment has recently undergone scrutiny, largely because of self-titled ‘The Anti Ice Man’ Gary Reinl’s publication ‘Iced’.